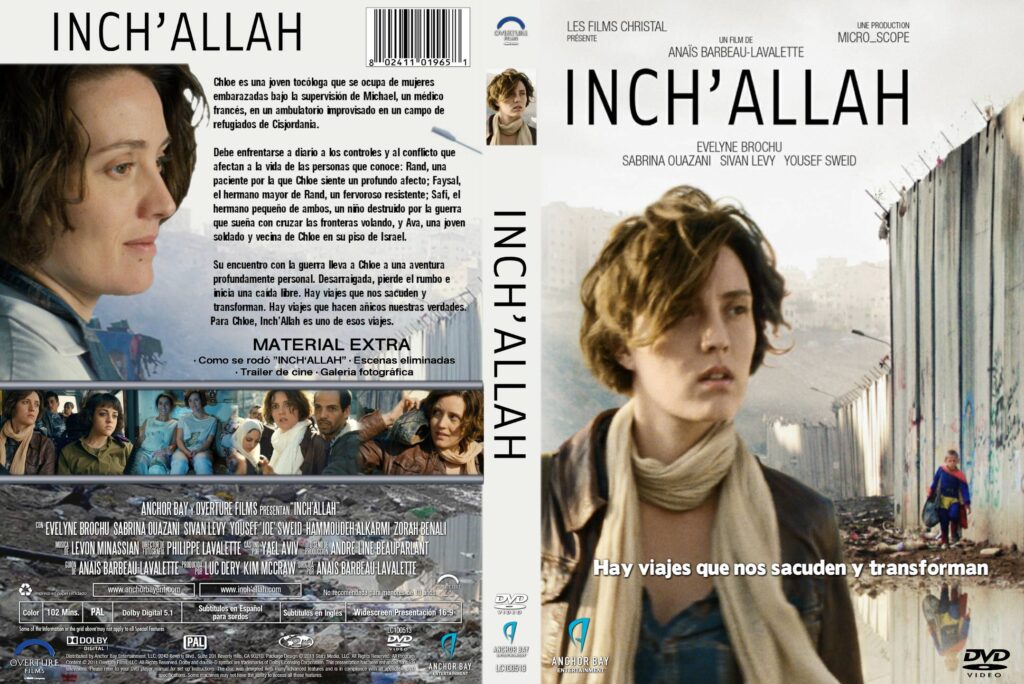

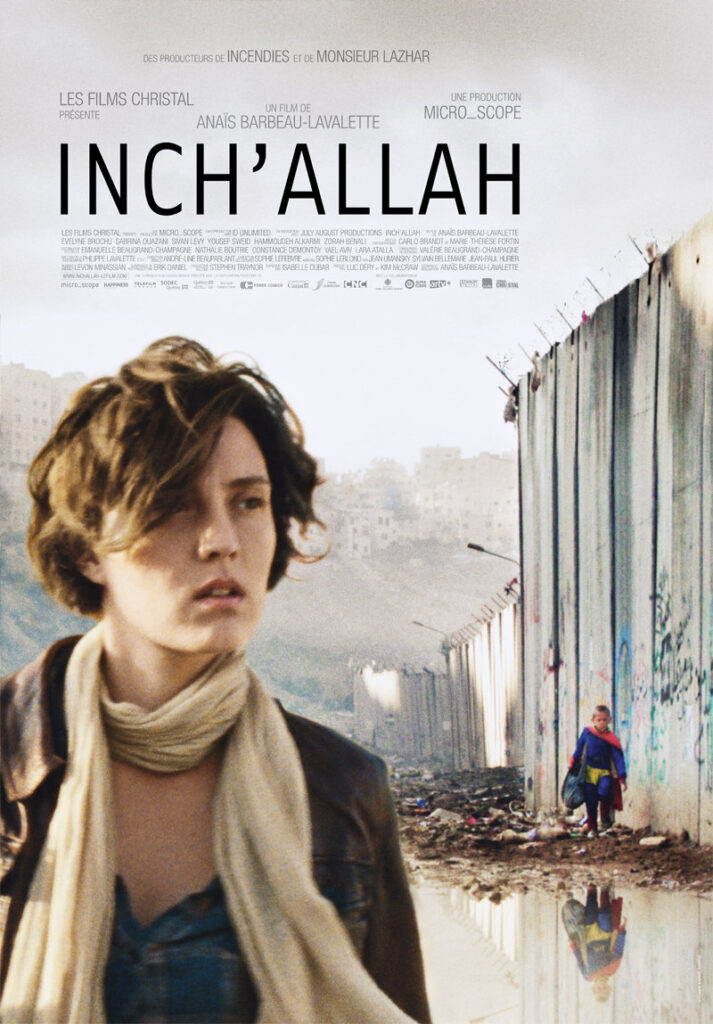

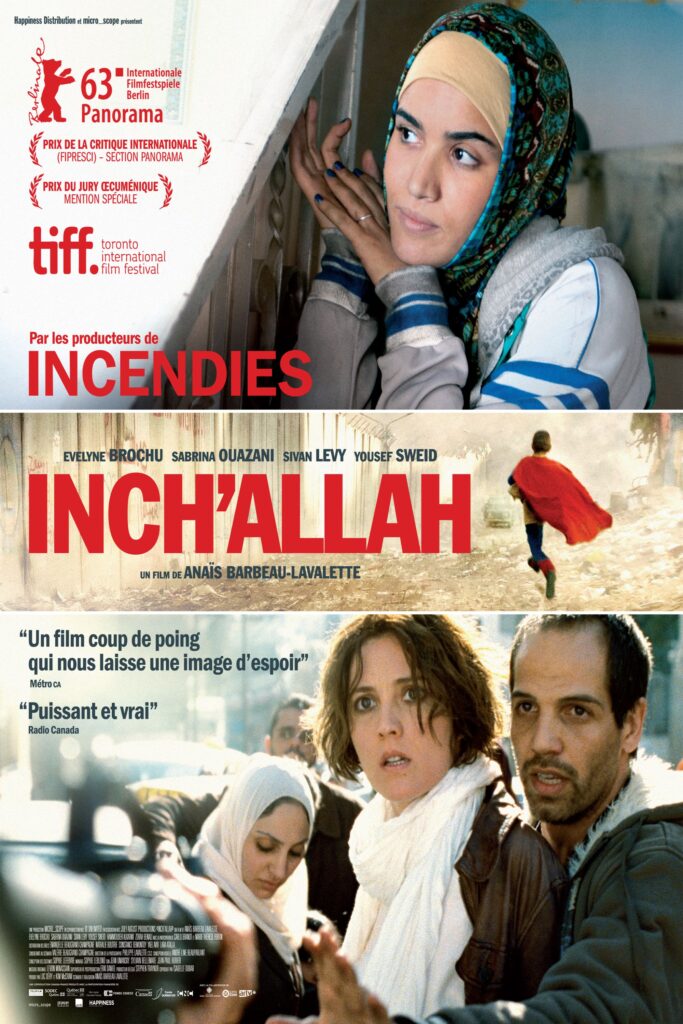

The walls of apartheid and the shattered dreams of Peace: “Inch’Allah” and the cinema of blasted hopes.

INCH’ALLAH (2012, Canada, 82 min, by Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette) is a tremendous film – and to re-watch it nowadays, in October 2023, as the humanitarian crisis and war crimes skyrockets in Palestine and Israel territories, it’s a must. One leaves the screening as if he just survived an earthquake.

To say that Chlöe and her (mis)adventures, wonderfully performed by the actress Evelyne Brochu (also a singer-songwriter from Montréal, Québec), is an “rollercoaster of emotions” would be an under-statement, and a bad cliché. What this film does with is compelling storytelling is blast upon our collective consciouness with the power of imagery to tell a tale that I’ll never forget and that we should all take heed, pay attention, open our hearts to be blasted by it.

I’ll try to share the whys that lead me to deem this an excellent film with a director and a lead-actress that have both done genius jobs: Inch’Allah feels urgent and relevant more than 10 years after release. It tells the plight of Chlöe, a Canadian doctor that moves from Québec to the Middle East; she works in Ramallah helping out pregnant mothers and women with small children, trying to develop a work in medicine together with humanitarian group <Red Crescent>, and also working in United Nations facilities etc.

But, even tough she works in Palestines, she lives in Jerusalem, sharing a flat and a tense friendship with Ava – which works as soldier for the Israeli Army and is currently on the border-police. Let’s put it like this: Ava works for the apartheid-state as one of the employees of zionism, guarding the walls that divide Israel and Palestine, and Chlöe is the one that needs to pass through day after day, moving from Israel and Palestine, forward and back.

This relationship is very interestly depicted in the film and would already make this artwork worthwhile, but things get even more interesting when we take a peek at Chlöe’s relationships with the palestinians. Chlöe, besides the merely professional relationship of “medical aid” ends up making friendship with the Rand family – the mother of one is pregnant and set to deliver her second son pretty soon. Chlöe is there in order for Rand to deliver her baby safely – and yet this film bursts into our consciences with no mercy, shattering our hopes, one after one.

Ths is cinema rising up to its task of powerfulness – not an art that “depicts” or “mirror” so-called Reality, but a power to act, a potentiality for agency.

This film has been for my taste one of the most blastful experiences I’ve been through: certain scenes explode our indifference with unmercifulness – a mother rushes to the hospital, but the Israeli blockade impedes her passage, she goes into the labours of birth on the back of a car in the middle of a traffic jam. Nothing around her serving as an apparatus of reception for the new-born in the human world in the hospital-setting, doctors and nurses, appropriate facilities e remedies etc. No, this is daily tragic unfolding in apartheid shattered land – and anyone paying attention to 2023’s “escalation” of violence opposing Israel vs Hamas (which, once again, downspiraled into Israel unleashing genocidal military powers against Palestine sent to the extremes of the conditions of life we might call “oppressed”.

Inch’allah deserves to be seen because it furnishes depth and width, flesh and pathos, to the oppressed people living in Palestine. It’s available for moviegoers who aren’t craving for escapism but striving to learn about the world and how to act upon it wisely.

This film starts and ends with a tremendous blast, and it’s a genius narrative structure: it’s the same blast – a person blowing to pieces in a suicide-bomber terrorist attack – and yet the blast at the end has a transfigured meaning. It has layers of significance which were absent from the first scenes.

What Chlöe lives through, in her flesh and blood, if we watch with empathy enough, sends us on a journey where we can’t possibly judge the first blast of the film as the same event as the last blast – and yet, they are the same event, told at the beggining of a narrative and at its ending.

The film provokes thoughts about jobs that need to be done, and yet are quite difficult, disgusting, or too heavy on the nerves, for the common human to accept it. We shouldn’t call them Bullshit Jobs, in David Graeber’s language, because they’re something also: almost-impossible-jobs that are also extremely relevant. The film’s protagonist is a Canadian woman from Québec that works as a doctor in Palestine and gets crushed into severe trauma by what she lives through there. To put it simply: “it’s a dirty job but someone’s gotta do it”, you’ve all heard this mantra before, and yet most of the times we can’t have access to the traumatic lived-experience of the people who do this almost-impossible tasks. Then steps in cinema, an art in general, to mediate to us the lived experience in other, to make it understandable for us.

The dirty-ness of the job in question lies in the political realm: she’s a female doctor in an apartheid society ruled by patriarchs, and where all around her religious fundamentalism rears it ugly and violent head.

She soons discovers, upon arriving to work in medical aid, that Gaza is filled with children, swarms of kids whirlwinding like small tornados at the shadow of the Wall. Kids playing with porno mags, treading shoeless amongst ruins and rubble. Kids who grow up with rifles and tanks of an enemy army constantly menacing them.

They’re unruly, anarchical, wicked children – dows that mean Israel should be allowed to slaughter by the thousands? Infancy, however unruly, and even it ventures into Intifada, is never to be teatred as incurable – they’re just beginners – but powers-that-be that deem themselves entitled to murder children by the dozen with their high-tech missiles and bombs.

In this film, there’s nothing kitschy about infancy. By mid-screening, the espectator gets a punch in the eye. That of course by chain reaction hits him on the brain – and then shakes his heart out of any confortable bubble of merciful oblivion about what apartheid really means by those suffering it. It blast upon the screen a lesson about palestinian kids under apartheid.

Neither Chlöe nor ourselves will ever be the same after witnessing such an event. Cinema is a great apparatus to get to the concrete, to descend from philosophy’s sometimes very high and lofty abstractions, and I wanna get down to the job of our protagonist in more detail, for example the check-points she has to go through: to be allowed through the barriers offers her a sense of privilege mixed by that of victimhood – but because she, in solidarity with the palestinians, also is humiliated and stressed by the Israeli armed-imposition of check-points to enter and leave Israel.

She’s a white woman from Canada, and the operators of Apartheid-state don’t have much reason to suspect her of aiding armed jihadists, so she goes through relatively easily… until the day – here comes the punch in our retinas, the aggression to our empathy-filled hearts – when one of the boys she knew gets crushed and murdered below the enemy’s tank. Chlöe will then be lead to help the palestinians in denounciation of this horror through posters glued all throught the bloodbathed “holy lands”…

Infancy here – Palestinian childhood – breaks the scene and wants front stage – and it screams in rage at our minds, and the films conveys all this horrorism which has in Italian thinker Adriana Cavarero all of the best decipherers.

The film is about the trauma that this kid’s death makes upon Chlöe. Her mother, on a video-call, notices the her daughter is depressed, and kinda silent. The mother asks her the common questions of what-happened? and whats-going-on, but she refuses to speak.

The trauma of the violent death of the other, in case, a palestininan kid with whom she had just “played” – in very homo ludens style – amidst the piles of rubbles, pretending they were calling Israel’s prime-minister through an abandoned boot, made to look like diplomatique telephone line. She remembers playing joyfully with this kid she has just witnessed Israel’s tank slaughter.

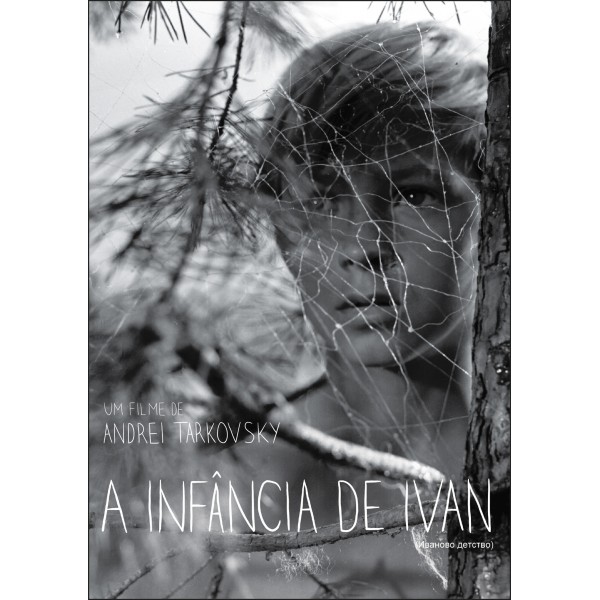

Tarkovsky made us suffer Ivan, child lost amidst the chaos os war. Anais Barbeau Lavalette, in her film, makes her protagonist suffer her own “Palestinian Ivan” – and she fears – we can sense it so strongly in Eveline’s marvellous performance, with a face of expressive pathos that can’t possibly leave the spectator undisturbed – that other tragedies will befall other children.

She discovers, and by her discovery the film delivers to us, the fact: a plurality of children, and the women who gave birth to them, are menaced by this apartheid-situation. Not matter how hard Chlöe tries, of course, she’s impotent to radically change the situation. But she remedies it, she helps cure the sickened, heal the bruised, amidst blood and suffering – the Sisyphos job of being a doctor in Palestine.

Not an heroine from Marvel. She’s got no special effects from the team of Avatar. This fleshy and bony Canadian woman, extremely beautiful in her trauma-disturbed dynamic visages, is struggling with a task that might crush her mind and mental sanity so badly she’ll end up shouting “mommy, get me back to Canada – right now!”

Blastful tragedy impels her to leave. Before we met her, our protagonist, the film had begun with a prelude – in Israel, we see a kid in what seems to be a market, and then “boom!”; so here’s enough proof that this film isn’t affirming that only Palestinian kids are victims here, it adresses the terrible evils befalling the youngsters on “both sides of Wall” inside this apartheid-regime.

But we shouldn’t also mistake the message in its blastful ending. In its final chapters, Chlöe fails to help deliver Rand’s baby. Stuck in a traffic jam caused by the Israeli Army blockade, the improvised birth on the back of the car turns sour. When Chlöe is hurrying to take the newborn to the hospital, the baby dies in her arms. She collapses into tears. A few moments ago she had just screamed at the soldier who wasn’t letting the doctor and the mother on child-bearing labour through – and the soldier had used his rifle to silence her and send her away.

This film teaches us deep, important lessons about the process-of-becoming of the “suicide bomber”. No one is born a suicide bomber, one becomes such a “thing” after a life-trajectory that we need to understand rather than condemn. The film gives it flesh and context, it teaches us how Rand could become a suicide bomber because of all the traumas imposed upon her by life under apartheid.

This mother with shattered hopes, tired of seeing kids dying prematurely, slaughtered by the Israelis and seen as “collateral damage” of zionism’s “holy war against the axis of Evil and the new nazis” of Hamas, ends up becoming what corporate media would call “a terrorist”. Rand’s dead baby will ever afterwards be haunting the mind of anyone who has seen this film and dares to express opinions and judgements about Israel and Palestine.

Through the aesthetic experience of Inch’Allah, we could suffer what Rand suffered in the process of becoming that act of suicidal and homicidal terrorism which no inner nor innate evil in her core led to commit.

Her evil is only explainable by the lived experiences she went through, and her religious justification could be delusional – yes, she might be killing herself for a God that doesn’t exist, while killing civilians in Israel, including other kids, leaving other traumatized mothers along this sad trail of unstopable aggression, and so yes, her act could be judged as profoundly evil. But I must insist on buts.

But… the tale the film has told makes us understand her (Rand) better than we would otherwise “understand” what happened to the person who became what is named terrorist; mediated by Chlöe, artistic diplomat between two warring worlds, we somehow met Rand and Ada through the mediation of Chlöe, we saw the abyss and the walls that separate them, and how failure also traumatizes Chlöe – after all, powerless doctor, silenced citizen, underachiever as human rights activists etc.

But… the dead baby of Rand, in Chlöe’s arms, blasts upon the screen and imprints itself in our lived-experience mediated by art. And then we might undestand the rage and fury of Rand as a mother who feels that her baby has been killed by a system she has now decided to blast. It’s terrible to see Rand rage against Chlöe, in cruel ingratitude, “go back to your land, bitch!” – but we must understand that instead of quiet mourning she chose blasting out in rebellion, in self-sacrifice, in a feast of death – which for her perhaps will open the gates of Paradise, Inch’Allah. The faithful hope that Allah will provide for her and the loved ones an afterlife Paradise to reunite them all gets embodied here in this young mother that only goes to such ethical extremities as a suicide bomber because of oppressions and traumas suffered.

In this tremendous, impactful film, Inch’Allah, we have all the powerfullness of an artform – cinema! – put in service of blasting hopes and shattering peace in order to help us see better a wise way out of this mess. It can be read as a parable of the vicious circle we find ourselves, once again, locked inside and producing such terrible slaughters. To learn to leave this vicious circle is a task not only for Palestinians and Israelis, but for humankind – and atheists, agnostics, sceptics and faithless people should also be invited and welcomed to participate in a debate about how would we construct a virtuous circle out of this nighmarish bloodbath we return and return to. Each sect claiming it has God on its side.

And yet, despite dead babies, crushed-behind-the-tanks pre-adolescents, traumatized doctors leaving back to Canada, and terribly bruised palestinians moms that become Hamas-affiliated suicide-bombers, this film has the absolute genius-daring of providing us with some horizon for bettering. With some tiny utopia, some tiny rays of light. Refusing total despair, the film teaches about radical action but also about social work done in courageous resilience. It leads us into the extremities of agency, and warms us about the trauma of failed labours, and yet makes us wonders at the insistence of these new Sisyphos. They keep on keepin’ on, doing the impossible jobs.

A small rock in the hand of an oppressed kid that insists on banging it against the wall of his Gaza-prison seems to manage to open holes – however small – in the apartheid’s walls. And a curious human eye, amazed at the world, daring a gaze that defies concrete walls and barbed wires, ventures into a better horizon. In his horizon – the film refuses to depict it with a subjective camera, choosing rather to focus on the kid’s eye looking through the hole in the wall – there’s something worthy of our esperançar, like Paulo Freire taught: not hope as wait, but hope as motor to combust tranformative action against all forms of oppression and apartheid. In his vanishing point the kid perhaps sees through the hole in the wall some trees bathed in a sunlight that shines upon us all.

Eduardo Carli de Moraes

Amsterdam, October 23th 2023

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

Amid Israel-Hamas War, Revisit ‘Shattered Dreams of Peace’

SAIL INTO THE PIRATE BAY:

DOWNLOAD THE FILM <TORRENT> <SUBTITLES>

DVD Rip – AVI – 1.474 Kbps

672 x 288

Frame Rate: 23.976 FPS

File size: 1.364 Gb

Publicado em: 23/10/23

De autoria: Eduardo Carli de Moraes